Your donation will support the student journalists of Ames High School, and Iowa needs student journalists. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

ANALYSIS: THE RACIAL ACHIEVEMENT GAP— NOT BLACK AND WHITE

February 14, 2018

Ames High is home to an array of talented students: from National Merit Scholars to All-State musicians and some of the best athletes in the state.

In August of 2017, the school-ranking website Niche named Ames High the number one public high school in the state of Iowa for the fifth consecutive year. The recognition for students’ hard work is motivating and something to be celebrated.

However, it is important to shine a light on a section of students who aren’t experiencing the same success.

When Ames High was first honored by Niche five years ago, the graduation rate for African American students was 53%. According to Dr. Anthony Jones, Director of Student Services for the District, there were “only [around] 20 African-American students” graduating that year, with over half of them not receiving their diplomas.

“We should have been able to… graduate twenty African-American students,” Jones said.

In addition to the graduation rate dilemma, another problem was brewing under the community’s nose. In January of 2017, the Iowa School Report Card showed an alarming gap in proficiency between black and white students in the District, based on math and reading scores from 2016.

When comparing the two races, Ames High had a gap in proficiency of 14%, with black students sitting at 81% and white students at 95.4%. The gap at the middle school was even more severe: only 53.4% of black students were proficient as opposed to 89.6% of their white peers.

The data was a shocking wake-up call for the Ames community. How did such a large problem stay hidden from the community long enough to become this startling? “We ignored it,” Jones said.

“This is a very high-achieving school district… Most people promote what they’re good at,” Jones said. “People don’t promote areas that they’re struggling in. Most of the things that were reported out were successes.”

UNDERSTANDING THE “WHY”

Before jumping to solutions for the achievement gap, it is critical to understand the scope of the issue and its significance—not only as it applies to our community, but to the nation.

Gloria Ladson-Billings is a pedagogical theorist, teacher educator, researcher and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the School of Education. Ladson-Billings is Chair of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, with the heart of her research examining teachers who successfully use various pedagogical practices with African-American students, as well as applications of the Critical Race Theory in education. One of her primary goals has been to push the emphasis away from the “achievement gap” and focus on what she likes to call an “educational debt”.

“Looking at our current educational problems as an ‘achievement gap’ forces us to look to the year-to-year progress on various standardized test measures and allows us to conclude that the problem lies solely in the realm of scholastic disparity,” Ladson-Billings said in her essay, “Pushing Past the Achievement Gap: An Essay on the Language of Deficit.”

That essay was a response to an address she gave during her time as president of the American Education Research Association. In her address, she broke up the “debt” into several parts, including social, economic, historical and political factors as contributors.

Ladson-Billings’ input, although aimed at the nation as a whole, is important for the District to internalize so that we can move forward with the understanding that this problem has had decades, even centuries, to amass and cannot be erased overnight, nor with one clear-cut solution.

WHAT SHOULD WE BE DOING?

When Dr. Jones arrived in Ames in 2011 as Associate Principal at Ames Middle School to discuss issues regarding race and cultural pedagogy, those conversations were not taking place.

“Now we are starting to have conversations about race,” Jones said. “You want to talk about how to close the achievement gap? Begin to talk about race.”

Because Black and African-American students make up only 8 percent of the total student population at Ames High, some may find it futile to cause a raucous over a small amount of students when the majority of students are doing well.

Unfortunately, we cannot think in this way. Each student who roams these halls is more than just a percentage; to neglect one group of students is to neglect all.

It is during daunting obstacles such as these where we should consider what it means to be a student in Ames. We should be proud of our achievements, but we should not allow certain students to fall through the cracks as others simultaneously see towering success.

What are we doing to advocate for the success and well-being of all students? How do we create an environment—from preschool and beyond—to allow this equity and success to take place? School-ranking sites can label us whatever they please; what matters is how we perceive our growth as a district in understanding, acceptance, and equal educational opportunities. This is when we see the gap begin to close.

“One of the things that we haven’t always done a great job of is looking at ourselves as an institution and what we need to change in order to have all students… be successful, including students who have traditionally been marginalized,” Associate Superintendent Dr. Mandy Ross said.

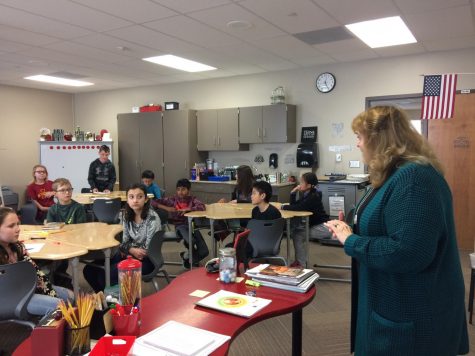

Jennifer Haglund, eighth grade counselor at the middle school, said she believes it’s important to facilitate student learning by helping them find their way rather than directing them. She also believes it is important to find out the ways in which individual students learn best, and accommodate them. “How do our students develop trust?” Haglund said.

Jones echoed Haglund’s statements, stating how important it is that teachers understand students on an individual level, then collectively as a class, before even focusing on instruction.

“Students [will] want to learn a subject because you want to learn about them, and now everyone is engaged and motivated to be successful in this classroom and move forward,” Jones said.

WHAT IS BEING DONE

As we work to reevaluate and redesign instruction and the ways in which students are served here in Ames, it is important to remember that this challenge is not just a task to be checked off. This kind of systemic change requires continual growth and improvement. “We really need to make sure we are addressing this work in a way that creates change, not just puts a band-aid on the symptoms,” Ross said.

“One of the things that we’re doing that’s new this year is that we’re working with Dr. Spikes and Dr. Swalwell from Iowa State University who have expertise in social justice and cultural competency… [W]e’re starting first of all with the school board, the central office administration and principals and assistant principals and instructional coaches as leaders in the buildings… Next year it will start moving into the teacher part of our organization,” Ross said.

So far, the trainings have only involved central administration and principals. Some teachers have expressed concern that they’ve been in the dark when it comes to receiving all of the necessary information, particularly because the teachers work with students on the front lines.

“The principals will be responsible for taking conversations back to the building after they have worked to understand the research, history, and best practices to address racial disparity in our schools… We are designing [a] three-year plan to be a systems approach. I am aware that some buildings have begun conversations with teachers, but the expectation is that all buildings will do so next year,” Ross said.

At the middle school, Haglund said that they have taken their building goals and broken up into vision teams. Haglund’s vision team focuses on “meeting the needs of all students” and have identified race as a critical need.

They have increased conversations about race and privilege, as well as biases and “[the] implication [they] have for… students.” So far, the operation has been at the grass-root level, but Haglund hopes it will ultimately become a systemic trend.

MOVING FORWARD

Teachers, administrators and counselors alike have expressed that having everyone working together is important to create systemic change. Changing the conversations we have—allowing conversations to take place that haven’t in the past—is also something that will allow us to move forward openly.

We have to make prevention our goal by starting early, but we cannot forget students who are already affected. This means working with families to ensure the success and equal opportunity every student in the district should be receiving.

“Until we begin to use the resources that Ames has in the community, we’re going to continue to see gaps,” Jones said. “We need to be more intentional about getting information [of substance] to our parents.”

Jones is primarily referring to things such as Infinite Campus, that are essentially our only channel of information from schools to parents. If the information that is being sent out is repeatedly of no relevance to certain parents, when something important comes along, they may skip over it.

“Families in the community, they’re aware of [the surplus of opportunities] but there’s a certain population who hasn’t been exposed to those things or have access to [them],” Jones said.

There also needs to be a reevaluation of inclusion across all buildings. The disparity in scores is an indicator of academic inequity, but the lives of students extend beyond the classroom.

“How do we make students of color feel about being in Ames? What have been their experiences in Ames? If we can get one-hundred percent saying [they] felt welcome [and]… a part of [the] Ames School District… that’s how I would define us closing the achievement gap and creating an atmosphere where all students are successful,” Jones said.

This sense of inclusion also ties into what is known as “culturally responsive teaching”, another term created by Ladson-Billings. It refers to a style of teaching that includes cultural references in all aspects of student learning. What are students being exposed to from a young age? Are they seeing people who look like themselves, look different?

“I would like to see us approach these conversations with an open mind, and not shy away from the reality that students experience the world in different ways, and it’s okay to discuss and examine the issues specific to any student, especially around race,” Stephanie Schares, ELP teacher at the middle school said.

This inclusion doesn’t just apply to students, however. Finding black or minority educators within the District is something of rarity. Jones understands this fact well, as he is one of the very few black and African-American teachers and administrators the Ames School District.

“There’s no support for [black] educators in Ames,” Jones said. “We don’t get a chance to get together and talk [about] what it’s like to be a staff of color in a predominantly white school district,”.

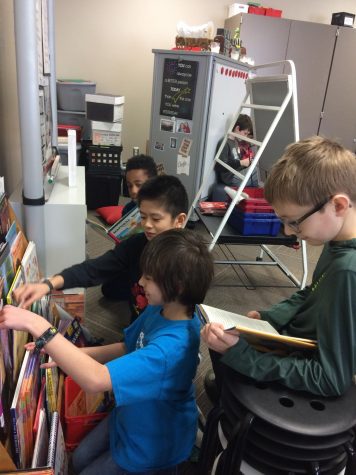

It is also important to understand that even though the gap becomes alarming at the middle school, it starts early. Mentoring Minorities is a newly created mentorship program between Ames High and Fellows Elementary for students of color to connect and help to provide reassurance for fourth and fifth grade students who will transition into middle school.

The program puts an emphasis on reading and allows the kids to have a friend who relates to their experiences and helps to cultivate self-confidence. SACRE (Students Advancing Civil Rights Education) leaders Isabel Ingram, Makai Muhammad, Melina Hegelheimer and Abbas Kusow envisioned and implemented the program that meets every Thursday after school.

Ultimately, “[w]e are not striving for equality we are striving for equity… Equity means everyone gets what they need, not just everybody gets the same thing,” Schares said. “Instead of saying, this opportunity is equally available, I’d like to ask, is this opportunity equitably available?”

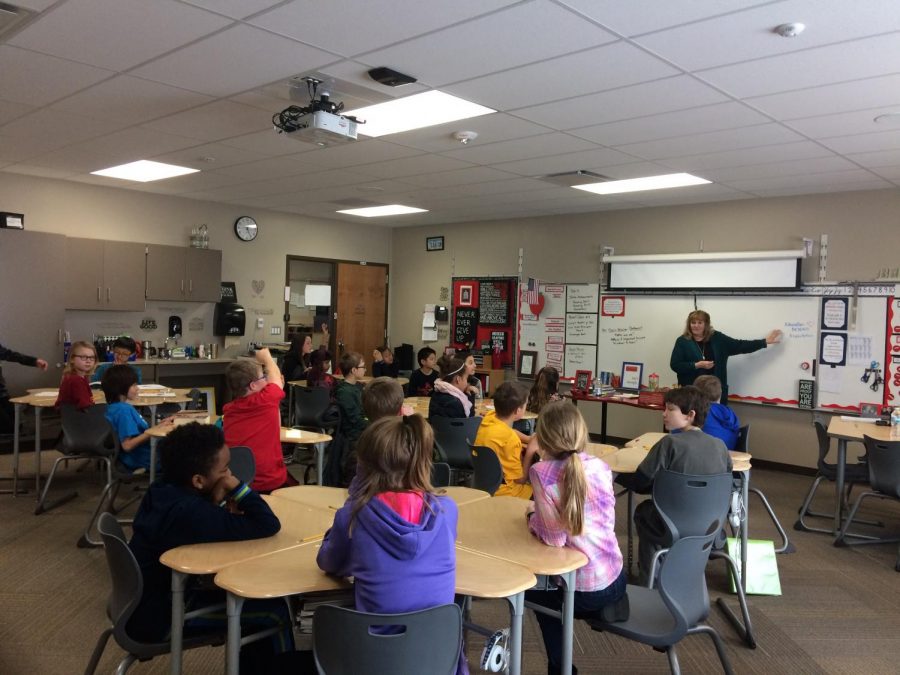

Inside Elise Wright’s 5th grade class at Fellows Elementary is a diverse pool of driven, fun-loving students. Among their apprehensions about middle school life are forgotten locker combinations, schedules and the intimidating 7th and 8th graders.

Those trivial concerns are exactly what young students should be worried about, and all that they should be worried about. As a District, if we want to chip away at this achievement gap, we must be there for them. All of them.