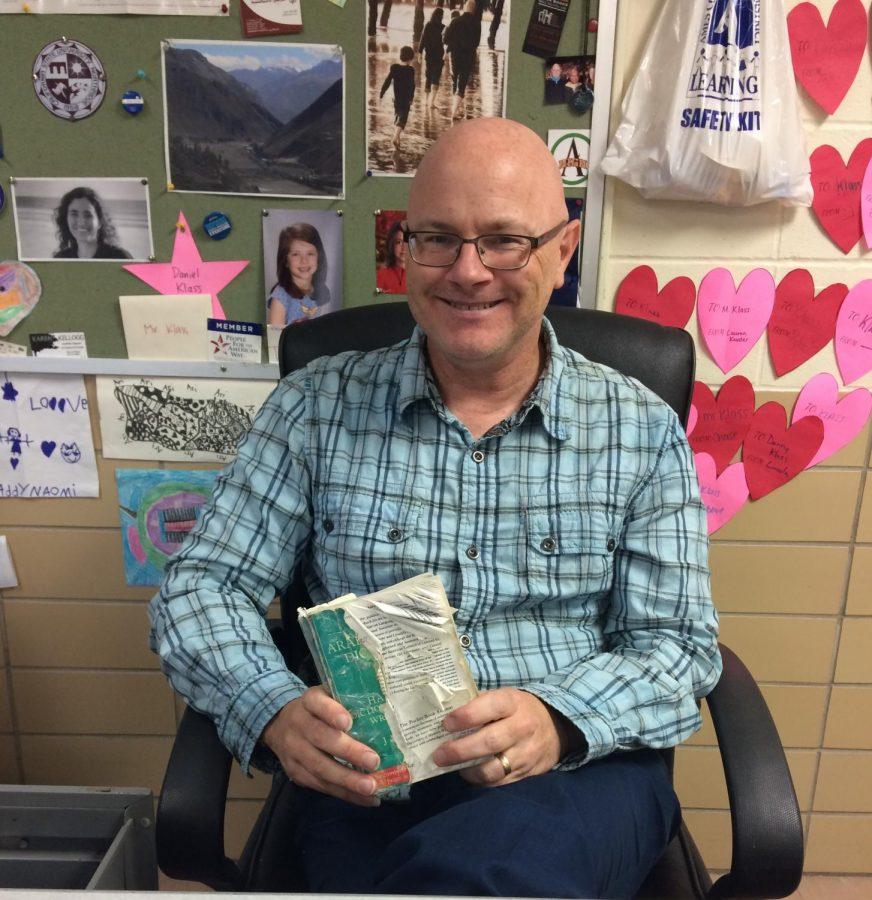

Teacher’s Hidden Talents: Around the World with Klass

Inside Daniel Klass’s drawer lies a book weathered from over twenty years of age. What’s left of the teal cover reveals the book to be an Arabic-English dictionary, the very first Klass bought while beginning his studies in Arabic in D.C.

After moving from a state school in California for his bachelor’s degree to a reputable program at George Washington University for his master’s, Klass couldn’t help but feel a bit overwhelmed. “I felt kind of out of my league in graduate school. I was in a pretty prestigious program and there were people around me who went to Ivy League schools,” Klass said.

For Klass, the dictionary is an artifact from that uncertain time in his life that reflected both doubt and discovery. “I remember pausing before I bought this and [thinking]… do I really want to do this?” Klass said.

Although he picked the Middle East as his region of speciality for his master’s degree in International Studies, there was no requirement to learn Arabic. Klass was going out of his way to enhance his understanding of the region, and, realizing this didn’t even tie in directly with his master’s degree, was unsure if he was making the right decision. With brief deliberation and a “what do I have to lose” type spirit, Klass embarked on a journey to learn his fifth language.

Originally from Los Angeles, California, Klass saw Spanish everywhere. Growing up in southern California, “[y]ou sort of know some Spanish even if you don’t know you it,” Klass said. Now, Klass can understand a lot of Spanish and speak a little as well.

Contrary to the popularity of taking Spanish at his high school, Klass tried his hand at French to take a different route than the majority of his peers. He didn’t know much about the language, but he knew enough to be intrigued. “I think what got me going in French in high school was that I was completely… over the moon with my teacher,” Klass said.

Before learning French, Klass had also learned some Hebrew. Compared to his knowledge of French, however, it didn’t compare. “I didn’t really learn it,” Klass said, “It was just… [in the] liturgical sense, like knowing the prayers.” Although his knowledge of Hebrew was limited, the exposure proved to be helpful later on in his Arabic studies.

Upon arriving to California State University at Northridge, Klass was essentially fluent in French. He took a semester in college, but due to a lackluster professor, he decided to call it quits. He then changed his major to political science and never looked back. However, his French skills were not lost on him.

After college, Klass backpacked with friends through Europe and the Middle East for over two months. The group visited almost 30 cities, including Paris, where Klass was able to hold his own and converse with the locals.

Moving to the polar opposite end of the country for his master’s degree, Klass studied international relations at GWU, and was met, once again, with the opportunity to use his French skills.

“Part of the degree was that you had to pass… [a] foreign language tool exam,” Klass said. “I thought, well… I guess I’ll just take it in French because it’s the one I remember the most. I started restudying and… that kind of got me back into learning French.”

After experiencing the Middle East during his time abroad, Klass became interested in the culture and chose to specialize in the region and learn its language. “I thought to myself, well, I think it’s a good idea that I start learning the big language of the Middle East, which is Arabic.”

Because the university didn’t have any Arabic courses, Klass learned at the Middle East Institute in D.C. The institute was founded after World War II and was a non-profit organization run by ex-intelligence officials, ex-government officials, and ex-ambassadors.

“They had a very robust language program in Turkish, Farsi, Hebrew, and… Arabic, and I thought ‘I’ll just check it out,’” Klass said. As Klass worked his way through graduate school, he spent a lot of time at the Institute and claims it had a large impact on him.

“In the back of the institute they had a library of only books about the Middle East and… that’s where I did most of my studying,” Klass said. He also had a great teacher and enjoyed the Institute’s townhome-esque setting.

After graduate school, Klass lived in Fes, Morocco briefly with a French-speaking Muslim family. At home, he spoke French, but during the day he spoke Arabic while studying at a local institute. Immersing himself in life with the locals, he expectedly began to pick up certain phrases and used them often.

“Inshallah means ‘god-willing’… Moroccans say it for everything. I found myself saying it so much, even more than Moroccan people were saying it,” Klass said. Although he likes the way it sounds, he is still curious as to what prompted his continuous usage of the word. “I don’t speak like that… in English, I’m not really that observant… religiously,” Klass said.

Klass attributed the shift from his typical word choice to his change in language, an idea supported by what he described as the Linguistic Determination Hypothesis.

“[Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf] suggested that… when we speak a language or read a language or are in that language, our worldview shifts and we see the world differently, and we act differently maybe,” said Klass.

“I’ve experienced [this phenomenon] because, for example, when I’m thinking or… speaking Arabic I feel myself become, for lack of a better word, religious, that I don’t feel when I’m speaking English,” Klass said, “and that’s because the language of Islam is certainly suffused into Arabic, they’re intertwined.”

Klass also elaborated that mistranslation of words to mean something less significant than what they truly mean is characteristic of the complex nature of the language. “There’s a phrase called ‘allah ‘akbar’ and it gets mistranslated all the time as ‘God is great’- it actually doesn’t mean that,” Klass said. “It means ‘God is greater’.”

“That gets to a little bit of the mindset when you speak Arabic that there’s a [sense] to kind of go beyond [and] to get into the realms of the spirit or the realms of religion,” Klass said. “There’s a kind of imaginative quality… that I can sense, and as much as I love French, it’s not quite there. It’s not really there in English either. It’s definitely there in Arabic.”

Klass’s life has had many exciting twists and turns, including living in Costa Rica with his wife and honing his Spanish skills, taking his Arabic students to Oman, and surprisingly, having two careers working for a non-profit and a newspaper before teaching at Ames High.

Today, Klass’s Arabic-English dictionary sits in his drawer small but mighty; even with its curled edges, ripped pages, and yellow tint, Klass admits he can’t bring himself to let it go, and understandably so. Years later, he is both infatuated and fluent with Arabic and the plethora of languages he has encountered and embraced- making his decision in the fall of 1994 a triumphant one.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Ames High School, and Iowa needs student journalists. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

Selaam “Mother Africa” Dollisso is continuing her journalistic endeavors as The WEB’s Online Managing Editor for the 2017-18 school year and she...